Key Takeaways from Past Outbreaks to Reduce Food Safety Risks in Caneberries

Earlier this month, before COVID-19 ended all work-related travel, I had the opportunity to speak at the 2020 North American Raspberry & Blackberry Conference in St. Louis, MO on the topic of food safety. For those of you who don’t know, I am the Northwest Regional Extension Associate for the Produce Safety Alliance (PSA), so this is what I do for a living. Something else you might not know about me is that I studied fruit for both my graduate degrees, so it was a special treat for me to address this audience and catch up with fellow students now working in industry and colleagues at land grant universities across the country. This post is an overview of my presentation. You can also download a PDF of my slides at https://cornell.box.com/s/6f8qgfk8xomtrdafmjle5v7uurqmy67t.

For those who’ve attended a PSA Grower Training, the micro 101 information is a review from Module 1. The biggest food safety hazards in fresh produce are human pathogens, microorganisms capable of causing disease or illness in humans. These include 1) the bacteria Salmonella, toxigenic Escherichia coli, and Listeria monocytogenes, 2) the viruses Norovirus and Hepatitis A, and 3) the parasites Cryptosporidium parvum and Cyclospora cayetanensis. Among the three categories, bacteria are unique in that they can multiply both inside and outside of the host (viruses and parasites can only multiply inside a host). If they have adequate food, temperature, and moisture, bacteria can multiply as often as every 20 minutes, producing millions of bacterial cells over an 8-hour time period. So our job as food producers is to make sure that we minimize situations that support bacterial survival and growth, and we accomplish that by employing Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs).

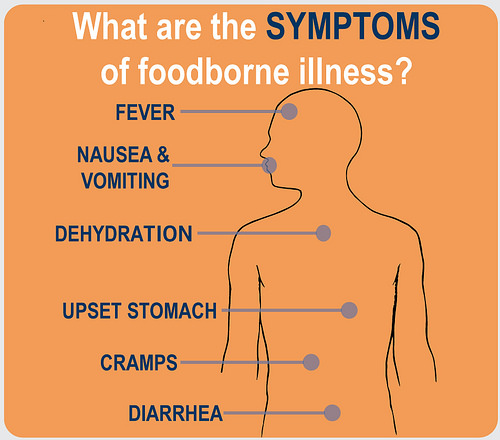

An outbreak is when two or more persons experience a similar illness resulting from the ingestion of a common food. Fresh and frozen raspberries and blackberries have been associated with several outbreaks in the last few decades. Notably, both fresh raspberries and blackberries from Guatemala were associated with C. cayetanensis outbreaks in the 1990s, and fresh and frozen berries have been associated with Hepatitis A and Norovirus. All the outbreaks I could find that were traced to raspberries or blackberries involved viruses and parasites which in otherwise healthy individuals usually only cause minor symptoms, such as diarrhea, nausea, or vomiting. However, in young, old, pregnant, or immunocompromised (YOPI) consumers, they can have more serious symptoms that result in hospitalization, long term health impacts, and even death. Luckily, none of these highlighted outbreaks resulted in death, but we don’t even want to make people sick. That would hurt our customers, our individual businesses, local markets, and the caneberry industry as a whole.

It’s important to note that freezing does not kill viruses. As stated by the FDA in a May 9, 2019 statement, “Frozen berries are used as ingredients in many foods and, like other produce, can be an important part of a healthy eating pattern. While frozen berries are used in pies and other baked goods, they are also used raw in fruit salads or smoothies and have been associated with outbreaks of foodborne illness. For instance, FDA reported three hepatitis A virus outbreaks and one norovirus outbreak linked to frozen berries in the United States from 1997 to 2016.” In 2019, FDA tested 339 domestic samples and 473 import samples of frozen berries (not limited to raspberries and blackberries) and found hepatitis A virus in five samples and norovirus in eight samples (FDA Sampling Frozen Berries for Harmful Viruses FY 19-20).

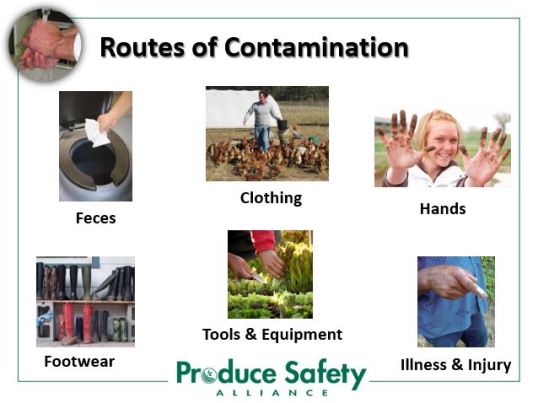

Berries may become contaminated with pathogens during production, harvest, packing, and holding, for example if handled by an infected worker who does not use appropriate hand hygiene or if exposed to contaminated agricultural water or a contaminated surface, like a harvest tote. Microorganisms are not easily seen, so contamination is difficult to detect, and berry surfaces provide great places for pathogens to hide, making them difficult to remove no matter how well you wash the berries before consuming them. For these reasons, the focus of produce safety is on preventing contamination from occurring in the first place.

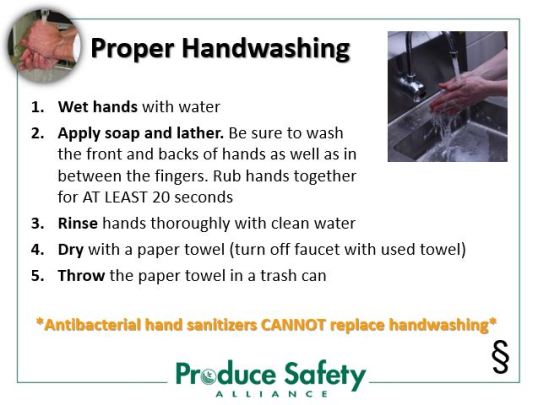

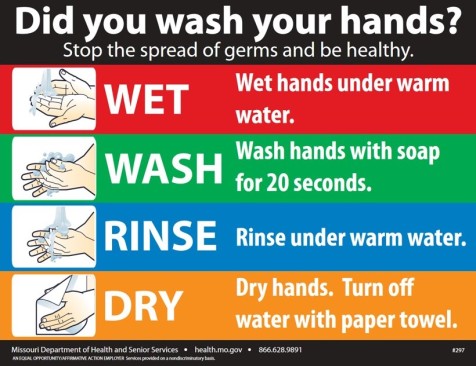

I spent the rest of my presentation time discussing GAPs that could have prevented four outbreaks. First, there was a Hepatitis A outbreak associated with blueberries in 2002. Contributing factors in that outbreak included an infected person present during harvest, inadequate handwashing facilities (no running water, soap, or hand towels), and harvesting with bare hands (no gloves). These are all addressed by the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) Produce Safety Rule which includes requirements for worker training, health and hygiene, and facilities that must be provided by farms (Subparts C, D, and L, respectively).

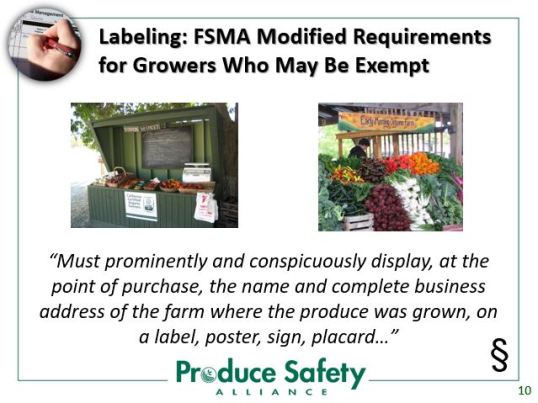

Next, I discussed an E. coli O157:H7 outbreak associated with one farm’s strawberries sold at roadside stands and farmers’ markets in 2011 (yes, outbreaks can occur on small farms as well as large farms). The contributing factor in that case was deer feces in the production field. Caneberries have an advantage over strawberries in that they’re normally trellised up off the ground, but harvest workers still must receive training to ensure that they’re not harvesting fruit that has contacted feces.

The third outbreak I discussed involved raspberries from Guatemala. As many caneberry farms do, the plants were irrigated with drip irrigation, which is low risk because it doesn’t contact the harvestable portion of the crop. However, the water used to mix pesticide sprays was contaminated with Cyclospora. This type of risk is addressed in Subpart E of the FSMA Produce Safety Rule, though the FDA has extended the Subpart E compliance dates so farms don’t have to start testing their water for indicators of fecal contamination until 2022-2024 depending on farm size. That doesn’t mean farms are off the hook – the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act prohibits the sale into interstate commerce of adulterated food. My key takeaways for caneberry growers were to understand the quality of water used to mix pesticides (or use potable water) and to train workers how to mix pesticide sprays to avoid contamination.

And the final outbreak I discussed was the 2011 outbreak associated with Listeria on cantaloupes. Remember, Listeria is bacteria so it can grow outside of a host. Unlike most other foodborne bacterial pathogens, Listeria can even grow under refrigeration, so again, prevention is key. In this case, the outbreak was traced to pools of water on the packinghouse floor and old, hard-to-clean equipment. My key takeaways for caneberry growers were to avoid standing water in buildings and to make sure that food contact surfaces of equipment can be cleaned and sanitized. In addition, I think there may be some benefit in picking directly into clamshell packaging as it reduces the number of surfaces the fruit contact (I acknowledge that this is not an option on all farms). Field-packing does require additional worker training and attention to detail so only high quality, uncontaminated fruit get picked and packed.

I summed up the presentation by asking the audience, “based on the outbreak examples I shared, what are some practices we can implement to reduce food safety risks and help us prevent future outbreaks in caneberries?” Here is a list of those practices:

- Wash hands

- Don’t work when sick

- Don’t harvest “poopy” fruit

- Don’t harvest dropped produce

- Keep fruit up off the ground

- Use drip irrigation

- Use clean water to mix pesticide sprays

- Avoid standing water in packing areas and coolers

- If using heritage or repurposed equipment, make sure it can be adequately cleaned and, if necessary, sanitized

- Clean and sanitize food contact surfaces